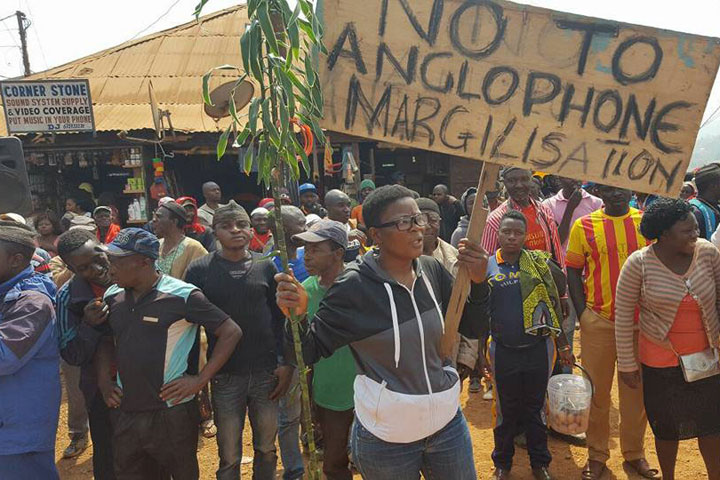

There have been increasing calls for independence among the English-speaking people of Cameroon as government ramps up crackdown on protesters

There is a separatist group in Cameroon, seeking for the creation of an independent, Anglophone State called Ambazonia. The separatists have gained more prominent in recent times as government neglects the demands of English-speaking people for equal rights and freedom of expression. A year of state repression has now undermined moderate voices and raised concerns the majority French-speaking nation may face a prolonged period of violence.

The struggle for expression has taken a dangerous dimension as soldiers shot dead at least eight people and wounded others in the two English-speaking regions on Sunday, the anniversary of Anglophone Cameroon’s independence from Britain. Amnesty International said on Monday at least 17 people had died in the clashes.

According to Reuters, the growing influence of the separatists, who include armed radical elements, is one of the most serious threats to stability in the central African oil producer since President Paul Biya took power 35 years ago.

The strife began in November, when English-speaking teachers and lawyers in the Northwest and Southwest regions, frustrated with having to work in French, took to the streets calling for reforms and greater autonomy.

Six people were killed in those protests, and in the months that followed, the government deployed thousands of police and elite soldiers, implemented a blanket internet blackout and arrested dozens of activists, dubbing them “terrorists”.

The thousands who protested on Sunday around the country were no longer calling for reform, but for a separate state for Cameroon’s nearly five million English speakers.

“We told them our problems. They responded with force, killing us,” said a young student in Bamenda, one of the largest Anglophone cities. “We need our own country.”

The true size and influence of the movement remains hard to gauge. Many leaders are in jail or exile, and it’s unclear how strong alliances are between a multitude of factions with competing visions of how to achieve their goals. Few analysts believe a split is imminent.

There is no doubt the separatists’ popularity and ability to stir turmoil has grown, however.

Separatists told Reuters that they were responsible for an improvised bomb that last month wounded three policemen in Bamenda.

“Nothing great can be achieved by using verbal excesses, street violence and defying authority. Lasting solutions to problems can be found only through peaceful dialogue,” Biya said in a statement on Twitter following Sunday’s violence.

An uprising by Biafran separatists in neighbouring Nigeria in the 1960s sparked a civil war that killed around 1 million.

The roots of the divisions go back a century to the League of Nations’ decision to split the former German colony of Kamerun between the allied French and British victors at the end of World War One.

The French Cameroons gained their independence in 1960 and the British Cameroons voted in 1961 to reunite with them under a federal government. The federation was abandoned a decade later, however, after a referendum most Anglophones considered a sham.

A separatist movement existed for decades underground, with activists sometimes communicating by passing notes to bus drivers going through different towns. It simmered but never gained widespread popular support – until now.

Southern Cameroons political activist Mark Bareta said government arrests of key organisers in January and February have pushed independent separatist coalitions, many of which are run by diaspora Cameroonians, together to form the Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Consortium United Front (SCACUF).

SCACUF and other groups are busily laying the groundwork for a new state, coordinating protests, gaining support on the ground, and – in some cases – orchestrating violent attacks.

They have printed thousands of light blue passports for Ambazonia – the Anglophones’ aspirational independent homeland – designed a currency and written a national anthem, five members told Reuters.

In May, they set up their own satellite television network, the Southern Cameroons Broadcasting Corporation, which reaches up to 500,000 people, said SCBC board member Derric Ndim.

Its satellite transmission is not affected by government-enforced internet cuts, he said.

“We are working to make a new country, and we are ready,” said Nigeria-based Julius Ayuk Tabe, chairman of the Governing Council of Ambazonia, which is spearheading the movement.

“The cries of the people are getting louder.”